Comfort is a Social Construct

And the AEC (architecture, engineering, and construction) Industry has, shall we say, a lot of opportunity to improve it's accounting of the social.

✳️ ✳️ ✳️ ✳️ Comfort is a social construct. ✳️ ✳️ ✳️ ✳️

Full stop. Yes, environmental and individual physiological and psychological factors are inherent components of comfort, but the key to whether or not comfort is actually achieved (or other quality of life indicators from satisfaction to belonging) typically resides in the social realm. And this isn’t something the AEC Industry does a great job of recognizing or accounting for relative to occupant use of space or the design/construction process itself (though this piece will focus on the former).

In shared spaces, our decisions to modify the environment (via shades/blinds, fans, moving furniture, etc.) are rarely a simple individual response to physical discomfort - they’re shaped by stress, group norms, proximity to controls, as well as the other people sharing these spaces. I recently came across the following conference proceedings paper - Social factors driving adaptive behaviours for indoor comfort: Towards a framework for effective integration - that analyzed this using a small study. It found that discomfort (from temperature, noise, light, and smell) triggers the following socially mediated sequence (at least for the occupants engaged in this study):

Discomfort (potentially causing distractions or interruptions) → choosing whether or not to consult with colleagues → action (adjustments to building and/or behavior) or inaction (live with physical discomfort). Though see figure 2 in the paper for a more comprehensive flowchart of the sequence.

Throughout this, norms, stresses, physical location, access to controls, and the social dynamics among the occupants all influence how the sequence unfolds, and they often steer people toward conformity (to avoid social discomfort) and tolerating physical discomfort as opposed to taking action to alleviate their physical discomfort.

While the study has its limitations, including such things as a small sample size composed predominantly of occupants who identify as female, limited information on other demographic factors, just one building occupancy type, no ethnographic component, etc., the results align with the work that I and BranchPattern have been doing for years. Let’s look at this briefly relative to thermal comfort, daylighting control in common spaces, and the relationship between indoor environmental quality (IEQ) and the microbiome.

Thermal Comfort

In our IEQ 2025 Conference paper, Why Thermal Comfort is Elusive: The Role of Socio-Cultural Factors, Stu Shell and I frame thermal comfort as a social construct, heavily influenced by the interaction of socio-cultural and technological factors (the interaction of the social and physical environments). Methods from the social sciences, like ethnography (discussed more at the end of this piece), can help us better account for socio-cultural influences equitably, resulting in design targets, sequences, interfaces, layouts, etc., that better reflect how comfort actually happens.

As you may have gathered, a significant amount of my interest in IEQ lies in it’s overlap with socio-cultural, relational, and individual behavioral factors (also quantifying IEQ related health and productivity impacts, but that’s another story - see Gaming the System and LEED vs WELL in Terms of Occupant Satisfaction). Such factors were the focus of Stu’s and my paper.

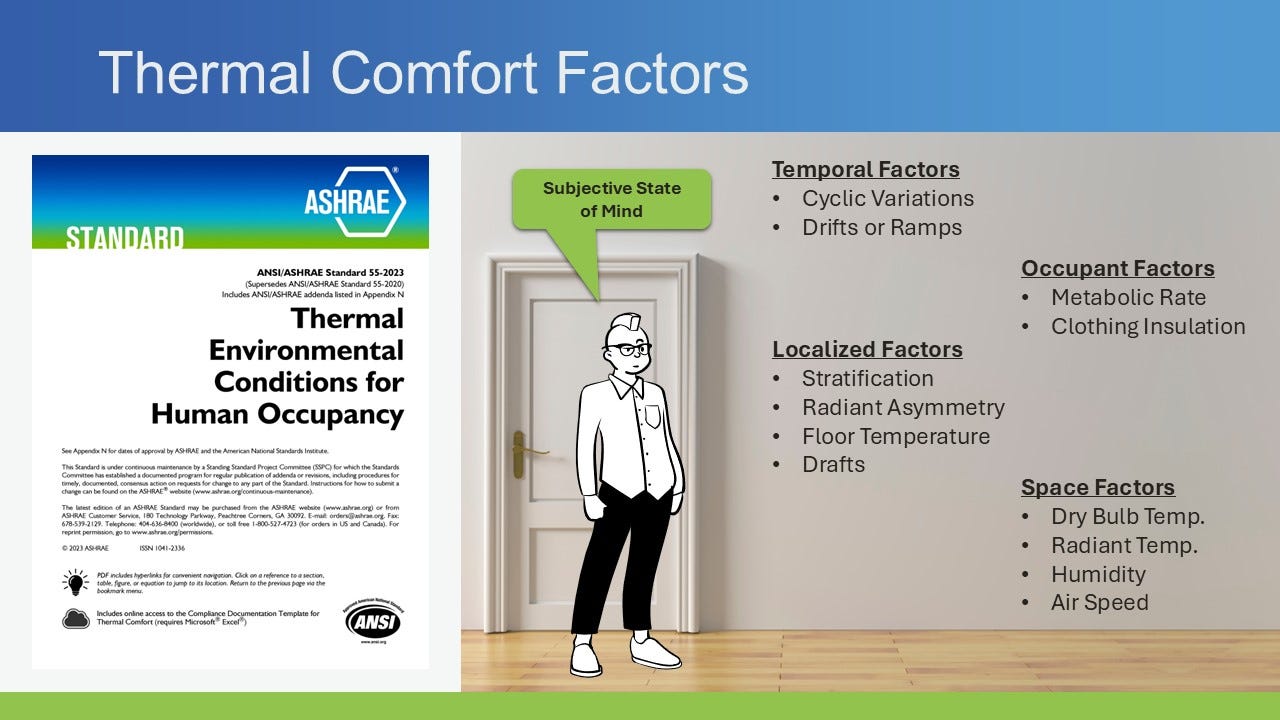

While our industry generally does an inadequate job of accounting for social and behavioral factors, I do think there’s increasing recognition that this is a deficiency. Below is one of the slides from the thermal comfort presentation. It lists the twelve factors (or eleven if you lump the temporal factors together) that ASHRAE Standard 55 defines as contributing to the subjective state of mind that reflects the satisfaction people have with their surrounding thermal environment. And while Stu and I are asking that we go beyond these factors, we recognize that as an industry we don’t do as an effective job as we should accounting for just these factors alone, or teaching how to account for them.

But regardless of how well we collectively account for these twelve factors, we still must do a better job of accounting for the social. And that’s because thermal comfort, or really most any experience within the built environment, is socially constructed. Thermal comfort isn’t just our physiological and psychological responses to the physical environment - it’s shaped by things like socio-economic background, socially defined activity levels, organizational policies, and clothing norms. Anthropology and other social sciences teach us that experiences, including comfort are relational, not just individual. For these disciplines, the smallest unit of study isn’t an individual but the relationship between two people and their environment. And we measure it by talking to people while they’re in their spaces, and observing them, making it a behavioral assessment in addition to a building performance assessment.

Measuring air temperature and relative humidity, the most common way that thermal comfort is addressed operationally in our built environments, isn’t just a small part of the thermal comfort story told by all of ASHRAE Standard 55’s twelve factors. No, these measures are also a woefully inadequate proxy for the real target of HVAC / envelope design – the occupant’s positive appraisal of their thermal experiences (and experiences overall). And our codes, design standards, and standard operational policies poorly address thermal comfort (and other aspects of IEQ) as a social phenomenon. So, there’s some work ahead of us to integrate the social into existing IEQ standards, best practices, etc., and the rest of the paper and presentation digs further into that.

Daylighting Control in Common Spaces

Daylighting control (along with the associated control of solar loads and view access) is often accomplished through the local, manual control of shades or blinds. But in common spaces, as the paper I referenced at the start of the piece stated, the availability and proximity to artefacts regulating indoor comfort (e.g. blinds, fans, noise-cancelling devices) as well as social dynamics within the work environment [or any environment], may either promote or inhibit actions aimed at achieving personal comfort. One’s visual and thermal comfort, as impacted by daylight and solar thermal loads, is socially constructed within common spaces when control is heavily managed via manually controlled shades or blinds. As I’ve previously written:

A common scenario for shades starting out the day raised is that at some point the amount of glare, high visual contrast ratios, and/or heat gain/loss becomes enough to override whatever shade adjusting social barriers exist, resulting in the shades over the offending glazing being lowered. But then, without any corresponding physiological discomfort to drive raising the shades, and through some combination of the social barriers present and inertia, the shades stay lowered, limiting daylight and view access from that point forward through the remainder of the day (as well as increasing the need for electric lighting). How long physiological discomfort is initially experienced before the shades are subsequently lowered to begin with depends on the nature of those social barriers as well as the degree of physiological discomfort experienced, tasks being conducted, and specific individual psychological factors.

Focusing on potential social barriers, different social factors impact one’s perception of ownership of the shades, and whether or not one can adjust them (or even ask others if it’s ok to make any adjustments). Employees with less tenure, employees visiting another office, contract employees, employees who sit farther away from the windows, non-residence hall students making use of the hall’s common spaces, library patrons, job categories with lower perceived status in an organization, and minority groups may all perceive less ownership of common shades (or other forms of common building controls) than other occupants present. Those who feel they have less ownership of manually controlled shades in common spaces will be less likely to make adjustments or ask those around them if it’s ok to do so.

The potential negative social outcomes from either bucking social barriers to take action or acquiescing to the barriers (e.g., tensions between employees, resentment, worry about the consequences of one’s actions, team and organization disfunction, etc.) can also negatively impact individual and organizational success.

Potential solutions (made more successful if informed by ethnography or some type of socio-technic pre/post occupancy evaluation), as I pointed out, consist of the following:

However, we can modify the social/cultural and physical environments to better align more of these different needs (physiological comfort, social/psychological comfort, organizational unity) with the nature and capabilities of the surrounding environments. Solutions to this could consist of varying combinations of a) the use of multiple shades of shorter width versus single shades covering large window sections or an entire wall (see shade photo below), b) an automatically controlled shade system with local manual override capabilities (though this too comes with its own set of issues), and c) implementing policy changes along with messaging (including signage) and education to manage expectations, reduce social uncertainties, and improve occupant use of the manual shades.

IEQ and the Microbiome

In another IEQ 2025 Conference paper I coauthored with Sarah Gudeman, Sarah Haines, and Stephanie Taylor, Connecting a Healthy Building Microbiome with Indoor Environmental Quality for a Sustainable Future (also presented at Greenbuild this year), we explored how the indoor microbiome shapes occupant health, resilience, and ongoing indoor environmental quality, focusing on everything from the impacts of ventilation and building materials on microbial communities to the role socio-cultural factors and inequities have in determining microbial exposures. And as we’re just beginning to integrate the indoor microbiome into broader IEQ research, practice, and standards (including moving towards a microbiome-based IEQ index), we have a chance to better integrate the social into this from the beginning. Some key aspects to consider include:

Socio-cultural Norms Shape Microbial Exposure: Personal space preferences, hygiene perceptions, diets, and cleaning practices and other relevant factors vary across regions, cultures, and organizations, differentially shaping microbial environments along with building operations.

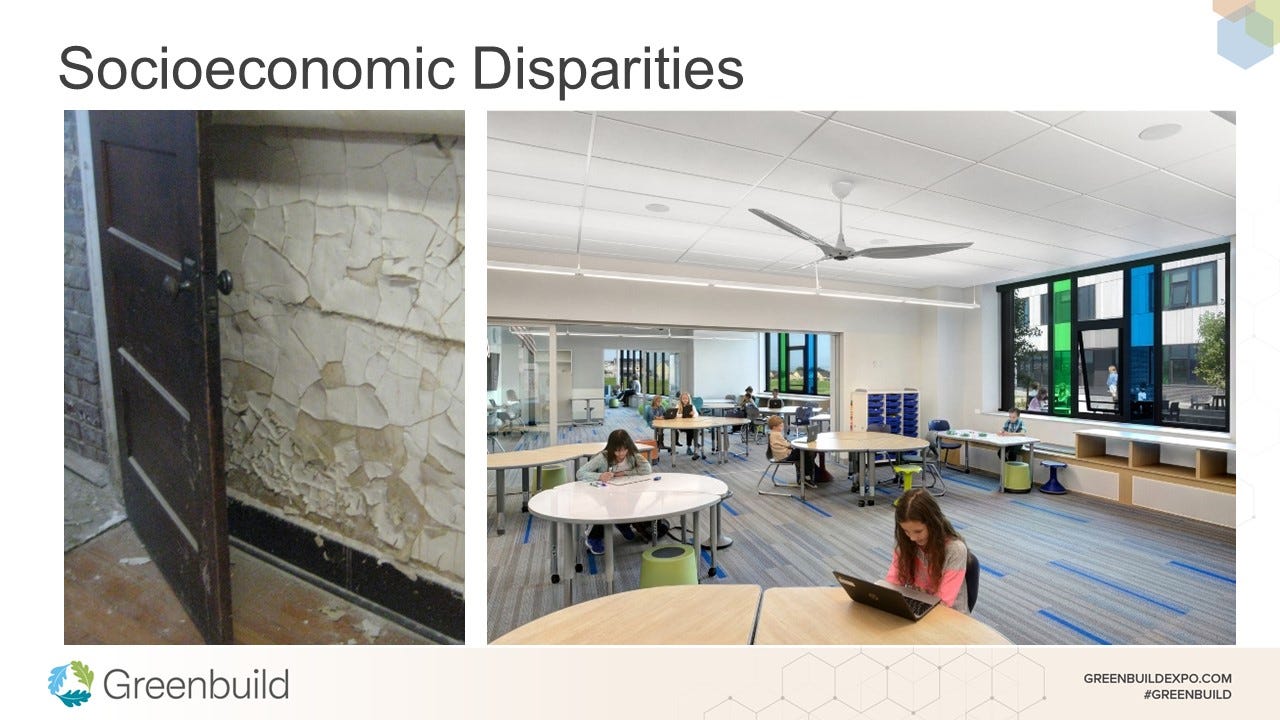

Socioeconomic Disparities: Lower-income communities face poorer quality housing, schools, and other facilities for multiple reasons, including deferred maintenance and limited operations capabilities. As a result they face higher exposure to pollutants and mold and have less resources available to address these challenges, increasing health risks.

Ethical Considerations: Microbiome “engineering” must prioritize such things as decolonizing microbial studies, incorporating the social sciences, community control of data to avoid reinforcing inequities, and even the rights of microbes themselves. For a really good overview of this see Can societal and ethical implications of precision microbiome engineering be applied to the built environment? A systematic review of the literature.

Viewing our built environments as living systems that change and grow allows us to place more emphasis on the lives housed by these environments as opposed to just the physical environments themselves. The goal - the ultimate targets - should be the quality of experiences - the quality of life - of the people (and other species) housed by the environments we design, build, and operate, not the various metrics related to the performance of the built environment (which are simply proxies for experiences, and sometimes bad ones at that). Focusing on living systems also makes it easier to include the social, which is important because the impact of human behavior on the health of the indoor microbiome, and subsequently IEQ and our own health, is socially constructed.

This focus on the social (relative to the design/construction process itself as well as building occupancy) also requires additional evaluation methods not typically performed in our industry (more on that below). And this results in relevant socio-cultural factors and nuances of interactions/behaviors being overlooked. One exception to this was the work presented by Sarah Haines during her opening keynote at the IEQ 2025 Conference - Community Engaged Frameworks Lead to Healthy and Sustainable Indoor Environments as well as the workshop that she co-facilitated with Natalie Clyke, Becky Big Canoe, Helen Stopps and Joshua Thornton: Indigenous Perspectives and Community-Led Approaches to Shaping Indoor Environments.

This work focused on understanding and addressing the higher rates of poor indoor environmental quality (IEQ) experienced within on-reserve housing. As Sarah stated, addressing these challenges requires more than engineering - it requires listening, collaboration, and culturally grounded approaches. And this is precisely what ethnographic methods are designed to do.

Ethnography

The second half of Stu’s and my thermal comfort/social paper and presentation covered ethnography - what it is and how it’s done at a high level, as well as four key concepts critical in it’s application - Context, Partnership, Interpretation, and Perspective. As a methodology, ethnography has it’s origins in anthropology, and it’s basically a systematic analysis of human interactions in a defined space and time, with a focus on performance (what’s going on and who’s doing it), power (who has it and who doesn’t), and ritual (habits, processes, procedures, and events).

Ethnographies are looking at the nuances of behaviors, the interactions of people, and the interactions of people with their environments. This provides additional insights into understanding how the physical + social/cultural environment influences the interactions and health/wellness of people, and vice versa. And I should note that the insights gathered and resulting solutions proposed sometimes challenge the status quo. This often results from including voices that have been previously excluded during planning, design, and operations.

If you want to dig deeper into ethnography and its applications I’ll refer you to the paper itself, with its greater focus on thermal comfort, or the following piece - The Power of People’s Stories - Using Ethnography to Improve our Built Environments - that covers its application within the AEC Industry in general. As an industry we should be engaging social scientists more, but short of that, short of formally conducting ethnographies, systematically applying the four concepts - Context, Partnership, Interpretation, and Perspective - to design and operations alone would increase our industry’s ability to create better, more equitable experiential outcomes accounting for the social.

And of course we need to be validating, quantitatively and qualitatively, the design and operational hypotheses shaping our built environments much more frequently and consistently than we currently do. But that’s a subject for another piece.

Great analysis