Design Implications of Entangled Sex / Gender Spectrums

Buck the binary and embrace entangled gender/sex spectrums - in design meetings, on athletic fields, and in our halls of government.

Anthropologist Agustin Fuentes, professor at Princeton University, has a new book out on the complexities of biological sex (touching on gender to a lesser degree) titled, Sex Is a Spectrum: The Biological Limits of the Binary. The book's publication is well timed, considering the current mis- and disinformation being spread about biological sex and gender, often cruelly targeting transgender and other LGBTQ+ individuals in the process. A brief book review is here and a more extensive discussion with the author can be found in a recent episode of the podcast The Dissenter. I haven't read the book yet, but it's now in my queue.

Dr. Fuentes's key point, as I understand it from the podcast episode and the book review, is that a binary view of sex is a heuristic categorization we humans overlay on a reality that is far more complex in nature (for all species, including humans). It's far more useful to look at sex-related characteristics as distributions instead of absolutes. Accepting this reality - accepting what science is telling us - while also being curious about the ramifications of this reality sets the stage for increased compassion and equity. And accepting this as reality also has design implications (more on that later).

Here's a brief summary of what some of the natural, medical, and social sciences have to say about sex and gender.

Biological sex is chemically and genetically more complex than XX and XY – it isn’t actually binary (and this applies to other species as well). From available sources (including some of what's listed below), those born with atypical genitalia (other terms used include intersex and ambiguous genitalia) range from 0.1% to 2%. With 8.2 billion people currently on the planet, then anywhere from 8.2 million to 164 million people currently alive today may have been born with some type of atypical genitalia. Biology, genetics, medicine, etc. do not support the statement that biological sex is binary (and Dr. Fuentes covers this is in great detail in his book). Here are a few other references:

While some of the literature will label these occurrences as disorders, it’s important to recognize that such a label has large cultural implications, even within a medical context that may also be attempting to account for associated health consequences – it’s a value judgement. Decisions made by parents (and adults later in life) relative to courses taken are heavily influenced by pressure to “fit” within a society that doesn’t understand or even accept the reality of their conditions. But they were born that way.

And gender, while influenced by biological sex, is also heavily influenced by cultural factors and societal norms. It is the inner sense of self as female, male, fluid, or some other alternative gender (though the specific details of how this manifests individually and collectively is still a subject of debate among experts and varies somewhat by discipline). But the social sciences overall do not support the idea that gender and biological sex are the same thing or that gender is binary (while still recognizing the entanglement between gender and biological sex). Here are a few references.

At one point during the podcast episode, Dr. Fuentes mentions that culture shapes how our brains develop as we grow up within a given society, influencing our perceptions of, and expectations for, gender and biological sex.

So, I mean, the bottom line is there's not male and female brains, there's a lot of variation. But, and this is, I think, really important and goes to what we were just talking about. When you look at brain activity in adults, Gender shows up very strongly, like, your masculine or feminine sense, your senses of man or woman, your senses sort of in uh uh someone who is not male, man or woman. That shows, we can see that in the brain, but you can't see that in kids. Um, AND so what's really interesting is that clearly the way neurobiology works is, as we grow up in a society in this gender sexed reality, it shapes our body and and our mind.

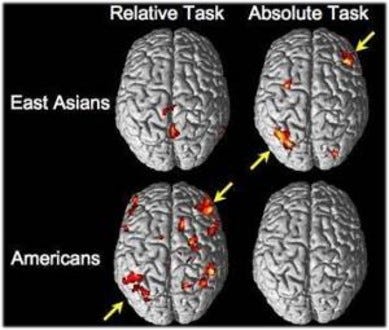

Years ago, in presentations I gave on the influence that socio-cultural factors have on our perceptions of the built environment, I used to reference a study (Hedden et al. 2008) conducted by a joint team from the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, State University of New York at Stony Brook and Stanford University. The researchers asked 10 East Asians recently arrived in the United States and 10 Americans to make quick perceptual judgments while in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner - a technology that maps blood flow changes in the brain that correspond to mental operations.

The researchers were comparing the brain activity of East Asians versus Americans as they were asked to make relative and absolute judgments. In the image below, the arrows point to brain regions involved in attention that are engaged by more demanding tasks. The Americans showed more activity during relative judgments than absolute judgments, presumably because the former task is less familiar and hence more demanding for them. The East Asians showed the opposite pattern.

The authors concluded that their findings supported the results of other research suggesting American culture, which values the individual, emphasizes the independence of objects from their contexts, while East Asian societies emphasize the collective and the contextual interdependence of objects. So, for example, an American looking at a photo of multiple buildings will more likely immediately focus on individual buildings and their characteristics while an East Asian will more likely immediately focus on the relationship of the buildings to one another. And that this supports the idea that the socio-cultural realms we grow up within shape how our brains are "wired" to perceive and interact with the world around us.

As I've written (Harmon 2012) previously,

As we learn, or are indoctrinated within a given culture, particularly as we’re growing up, our cultural surroundings, or “cultural scripts”, train our brains to use the basic psychological machinery we all have in different ways. This influences our perception of the world around us and what we consider normal behavior when interacting with others and performing tasks. Culture provides us with a lens through which we view and interpret the world, helping to generate our specific experiences. Culture helps us tell the difference between being comfortable and uncomfortable, thermally, visually, socially, or otherwise (e.g. Dourish 2007).

In the case of sex and gender, many cultures have forced a constraining binary view of sex that also often equates biological sex with gender (as many design standards and guides essentially do). As Ritz et al. (2025) recently wrote:

Of greatest concern for us is the tendency to conduct a binary female–male comparison, find a statistically significant difference between the two groups, and then make a recommendation that men and women function “differently,” or should receive different treatments, interventions, or policy recommendations.

This, no doubt, has contributed to the design and operation of environments many find physiologically, psychologically, and socially uncomfortable to varying degrees. The psychological and social discomfort many transgender people experience forced to choose between male and female restrooms in the public sphere likely comes to mind for many here, but we can also consider the physiological discomfort that likely results from inadequately accounting for the spectrum of sexual and gender characteristics that exist among humans (and can change over the life of an individual).

Morphological and physiological factors, including but not limited to skin-to-mass ratio, body composition, metabolic rates, and hormones (including the "sex" hormones estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone), and how they vary over the life of an individual, all impact thermal comfort. For example, estrogen enhances heat dissipation by promoting vasodilation (widening of the blood vessels), which helps dissipate heat through the skin. It also improves thermal sensitivity by lowering the threshold for sweating and vasodilation, making those with higher levels of estrogen (typically female bodied individuals) more responsive to heat, or less tolerant of heat (Fernández-Peña et al. 2023; Charkoudian et al. 2017). However, during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (when estrogen is high), female bodied individuals tend to have lower core body temperatures and may feel cooler.

But after ovulation in female bodied individuals, progesterone increases, raising the body's temperature by about 0.3–0.5°C (0.5–1°F), which contributes to reduced thermal comfort in warm environments during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. In male bodied individuals typically having greater levels of testosterone, the higher muscle mass and metabolic rates (driven by testosterone) result in greater endogenous heat generation (originating internally), and therefore a greater need to dissipate that heat in some contexts. But testosterone may also impact vasoconstriction (narrowing of the blood vessels) and sweating thresholds and rates, making male bodied individuals more heat-tolerant but less cold-tolerant in some contexts, in combination with larger skin surface area. These impacts of testosterone also decrease as male bodied individuals age and testosterone levels drop.

So, the impacts of these three "sex" hormones on thermoregulation appears to vary, sometimes significantly, within each of the biological "male" (XY) and "female" (XY) categories depending on individual factors and environmental contexts. Beyond that, the levels of these three "sex" hormones (and others) can vary significantly within each of these biological categories. The variation is great enough that DuBois et al. (2025) go so far as to call this binary lens a flawed characterization.

In fact, all hormones are present in all bodies, and there are dynamic patterns of natural hormonal variation across the lifespan, with considerable overlap in the expression patterns of most of these hormones between the female and male categories. In addition, hormone effects depend on patterns of hormone receptor expression and not just serum concentrations of those hormones. Moreover [and getting at the entanglement aspect], there are marked effects of social experience and environmental exposure on the expression of hormone receptors and regulation of hormone synthesis.

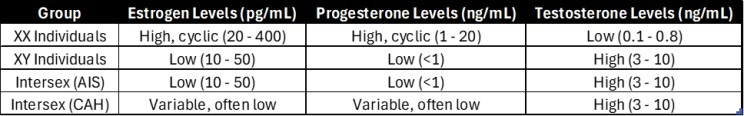

Returning to the podcast, at one point Dr. Fuentes points out that within the XY chromosomal category ("male"), testosterone levels can vary by as much as 300% between individuals. I had Copilot generate the following table for me based on a couple of studies (Hamidi et al. 2019; Paoli et al. 2023) to summarize some of this variation present within XX, XY, and two intersex manifestations. You can see that there's not only significant variation within each group but also occurrences of overlap between the different groups (sometimes significant). That means there's going to be variation and overlap relative to the associated impacts on thermal sensitivity and heat dissipation/sweating capabilities that doesn't neatly correspond to traditional biological male/female categories. It's also important to note that there's currently a lack of peer-reviewed research specifically addressing thermoregulation or thermal comfort in intersex individuals.

Note that AIS (Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome) refers to individuals typically having XY chromosomes and producing normal or high levels of testosterone, but their bodies are partially or completely insensitive to it. CAH (Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia) occurs with XX individuals, leading to excess androgen production, which can masculinize physical traits and alter hormonal balance.

On top of this variation in hormone levels and chromosomal patterns, we also have the complexity of body composition, skin-to-mass ratios, metabolic rates, and the further entanglement with gender that includes everything from clothing choices and other forms of gender expression to power dynamics impacting control over one's thermal environment as well as over one's body. And none of this consistently corresponds in a neat, non-overlapping manner to traditional WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) male/female categories (which themselves lack unambiguous definitions).

Yet ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55, and its underlying thermal comfort models, are shaped by historical research paradigms that reflect WEIRD populations and a binary understanding of sex and gender. One of the primary models, the Whole Body Thermal Balance Comfort (WBC) model or PMV model, (originally developed through research on WEIRD, college-aged students who were at least identified as men and women in Fanger 1972), was designed to predict the average thermal sensation of a large group of people, not to optimize comfort for any specific individual or subgroup (Mora and Bean 2018; van Hoof 2008). It uses standardized clo values for WEIRD and male/female-centric clothing ensembles that may not reflect the relevant gendered clothing norms for a given building population, or subgroups of that population. Metabolic rate tables also generalize activity levels without accounting for biological sex-based physiological differences in energy expenditure. Nor is the hormonal diversity found within and between groups, including intersex individuals, accounted for.

In the end, the model’s assumptions and parameters (e.g., metabolic rate, clothing insulation) shaped in part by WEIRD and a male/female binary biases, likely don't fully capture the physiological and behavioral differences that exist among any given building population. And by not accounting for this diversity of real-world occupants, the needs of many can be excluded during the design process. However, it is true that the standard's alternative Adaptive Comfort Model, based on world-wide field data, is a more flexible and dynamic approach, considering how people adapt to their environment through physiological (e.g., short term acclimatization), psychological (e.g., changed expectations regarding perceived control), and behavioral adaptations (e.g., opening windows, adjusting clothing types/layers) (Mora and Bean 2018).

But, as I understand it, while the original field studies that the adaptive comfort model is based on looked at 21,000 observations (occupant thermal comfort ratings, environmental measurements, and contextual/personal variables - clothing insulation, activity levels, and building types) from 160 buildings in different global locations, all of that data are essentially reduced to averages embedded within the model's formulas (de Dear and Brager 1998) - the model is based on regression analyses of this data to estimate the mean comfort response (e.g., neutral or preferred temperature) for the various populations under given conditions. The only variables actually accounted by designers during the model's applications via ASHRAE 55 are the operative temperature, prevailing mean outdoor temperature, and air speed; metabolic rates and clothing insulation values are essentially built into the formulas (having been implicitly accounted for through observed behavior in the field studies). Such averages (even if based on 21,000 observations from multiple countries) may not effectively account for the biological sex and gender variation present within a building population and their impacts on thermal comfort.

In addition, the limitations of this standard and it's underlying models are further compounded by designers, who are themselves trapped within the binary and applying it bound by their own cultural life experiences and cultural scripts, identifying as a WEIRD male or female. ASHRAE Standard 55, specifically when applying the Whole Body Thermal Balance Comfort (WBC) model, requires that each distinct group of occupants (based on activity level, clothing, etc.) be represented by one or more representative occupants. This is an individual or composite or average of several individuals that is representative of the population occupying a space for 15 minutes or more. But the designer's cultural blinders may limit their ability to fully account for the variation in biological sex and gender within a building population. A hypothetical example of this my colleague

and I pointed out in a paper (Harmon and Shell 2025) that we'll be presenting at the ASHRAE / AIVC IEQ 2025 Conference consisted of the following:For example, a middle-aged white male, who grew up in one specific U.S. region / climate zone, under one set of cultural norms, also trained as an engineer, may not immediately consider how the clothing insulation values of women wearing certain traditional Arab styles of clothing, such as the Burqa, may lead to their thermal discomfort in some spaces designed with Western standards and norms in mind.

This cultural binary lens (of the standard and designers) may not always be the dominant factor negatively impacting thermal discomfort. Plenty of other things may exert more influence here, from a facility's decades of deferred maintenance to applications of ASHRAE 55 without fully accounting for all of the factors impacting thermal comfort. But it does mean that the thermal comfort needs of, say, thirty year old cis-gendered males and females may be better met than those of transgendered individuals, intersex individuals, or female-bodied individuals undergoing menopause.

As Dr. Fuentes points out, there may be "... a general pattern [indicative of male versus female categories], but then when we ask the biologically or even medically [or even design] relevant questions, it becomes much, much less clear. And there's much more variation than we think." And Lian (2024), in his criticism of the PMV model for assuming a universal thermal response, calls for multi-dimensional, personalized models that account for the complex interplay of physiological, psychological, cognitive, and behavioral factors. He argues that current models, which rely heavily on thermal sensation, fail to capture the full range of human thermal experiences. While not explicitly addressing demographic variables such as gender, biological sex, or age, his call for individualized modeling implies the need to consider such diversity in future research and design.

And similar to how focusing on physiological, morphological, and behavioral averages while ignoring both the distinction between gender and biological sex as well as their entanglement can lead to the thermal discomfort of varying groups of building occupants, these can also lead to unjustly targeting transgender athletes. Dr. Fuentes recently pointed this out in an essay for the American Anthropological Association. The following quote from the essay is important to note:

The current focus on “sex” in sports by the Trump administration [and many GOP controlled legislatures, including Kansas] is less about biology and more about ideology, and a politics of exclusion and control. Of course, men and women are not the same and variation in reproductive biology shapes important aspects of human bodies and lives. And, across humanity there are a diverse range of gender/sex experiences. The bottom line is that different bodies and different life experiences can influence one’s performance in any given sport. The distribution of human biological variation as it relates to sport abilities, and everything else, is neither simple nor cleanly divided between the categories of female and male, boy or girl, or man and woman. As such, any serious interest and engagement with human bodies, gender, and sex diversity in most sports contexts must focus less on the acrimonious, and deceiving, framing of “an individual’s immutable biological classification as either male or female” and more on the actual data about human diversity.

And that diversity is something we should be celebrating, not vilifying, in design meetings, on athletic fields, or in the halls of government. Diversity - variation - this is the engine of evolution; it's a necessary component of keeping us thriving as a species and able to collectively face the adaptive challenges the universe throws at us. Diversity makes life endlessly fascinating - there's always something new for us to learn about the world around us and subsequently figure out how to apply it to our day-to-day (and/or just appreciate it in a state of wonderment). We still have so much room to improve how we #ImproveLife through #BetterBuiltEnvironments, and that should be energizing to all of us in the AEC Industry.

We should also be energized to work through the challenges of inclusive and fair athletic competition for all sexes, genders, ages, and abilities (while recognizing that many sports organizations have already been doing this for years). I recommend reading

's piece, The Moderate Case Against Transgender Sports Bans, for a really good take on this. On the surface, such bans can feel like an appeal to fairness and women's rights, but their arguments are full of strawmen and the reality is more complex and nuanced. Such efforts to ban transgender athletes can, and have, opened the door to more extensive attacks on the transgender community, including their right to exist.So embrace curiosity, exploration (scientific and other forms), understanding, and wonder. They can be good antidotes to fear, ignorance, and bigotry. As well as unhappy building occupants.

In addition to this substack I also write a LinkedIn Newsletter titled Anthro+Engineer→Bar. See the following for why I gave it this title. Sometimes I push the same piece out through both venues, but there are also pieces that live on only one or the other. I typically end pieces on the LinkedIn newsletter with a moment of humor. So, here’s the moment of humor that I shared on LinkedIn.

Staying on the topic of transgender sports bans, have a listen to one mom's take on the "athletic prowess" of her trans daughter, followed by John Oliver's hilarious take on it. Then go back and listen to the whole episode.

References

Charkoudian, N., Hart, E.C.J., Barnes, J.N. et al. 2017. Autonomic control of body temperature and blood pressure: influences of female sex hormones. Clin Auton Res 27:149–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-017-0420-z

de Dear, R., and Brager, G. 1998. Developing an adaptive model of thermal comfort and preference. ASHRAE Transactions 104(1):145-167. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qq2p9c6

Delli Paoli, E., Di Chiano, S., Paoli, D. et al. 2023. Androgen insensitivity syndrome: a review. J Endocrinol Invest 46:2237–2245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-023-02127-y

Dourish, P. 2007. “Responsibilities and Implications: Further Thoughts on Ethnography and Design.” In Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Designing for User Experiences. DUX ’07. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1389908.1389941

DuBois, L.Z., Ritz, S.A., McCarthy, M.M., Kaiser Trujillo, A. 2025. "Sex and Gender." In: DuBois, L.Z., Kaiser Trujillo, A., McCarthy, M.M. (eds) Sex and Gender. Strüngmann Forum Reports. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-91371-6_1

Fanger, P. O. 1972. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering. United States: McGraw-Hill.

Fernández-Peña, C., Reimúndez A., Viana F., Arce V. M., Señarís R. 2023. Sex differences in thermoregulation in mammals: Implications for energy homeostasis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1093376

Harmon, M. 2012. “Creating Environments That Promote Efficiency and Sustainability: Anthropological Applications in the Building/Construction Industry.” In 2012 ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings. Washington, D.C.: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/2012/data/papers/0193-000228.pdf.

Harmon, M. and Shell, S. 2025. "Why Thermal Comfort Is Elusive – The Role of Socio-Cultural Factors." In ASHRAE / AIVC IEQ 2025 Conference. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) and Air Infiltration and Ventilation Centre (AIVC). https://www.ashrae.org/conferences/topical-conferences/ieq-2025-conference.

Hedden, T., Ketay, S., Aron, A., Markus, H. R., and Gabrieli, J. D. E. 2008. Cultural Influences on Neural Substrates of Attentional Control. Psychological Science, 19(1):12-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02038.x

Lian, Z. 2024. Revisiting thermal comfort and thermal sensation. Build. Simul. 17:185–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12273-024-1107-8

Mora, R., and Bean, R. 2018. “Thermal Comfort: Designing for People.” ASHRAE Journal, February, 40–46. www.ashrae.org

Ritz, S.A., Bauer, G., Christiansen, D.M., Duchesne, A., Trujillo, A.K., Maney, D.L. 2025. "Operationalization, Measurement, and Interpretation of Sex/Gender." In: DuBois, L.Z., Kaiser Trujillo, A., McCarthy, M.M. (eds) Sex and Gender. Strüngmann Forum Reports. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-91371-6_5

van Hoof, J. 2008. Forty years of Fanger's model of thermal comfort: comfort for all? Indoor Air 18(3):182-201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00516.x. Epub 2008 Mar 24. PMID: 18363685.

From Erin in the Morning - https://substack.com/home/post/p-174025110: The Oversight Project at the Heritage Foundation (think Project 2025) is pushing to "... formally designate all transgender activism as 'Trans Ideology-Inspired Violent Extremism,' a new category of domestic terror threat."

This new definition "also includes anyone who argues that stripping away transgender rights constitutes violence or an existential threat to transgender people. That second prong is sweeping: by its logic, nearly every transgender rights activist or organization—merely for pointing out the tangible harm that comes from losing rights—would fall under the label of extremist."

"[E]ven the most basic act of advocacy—like pointing out that anti-trans laws threaten transgender people’s existence—could be construed as 'incitement.' The memo itself makes the danger plain: in its list of 'typical characteristics' of supposed extremism, it cites a trans flag with the words 'protect their right to exist.'"

----------------------------------------------------------

This article I've written on the design implications of sex/gender spectrums could be considered incitement under this definition. Advocating for the needs of the trans community during planning, design, construction, and post occupancy could be considered incitement. Basically, doing our jobs as professional within the AEC Industry - advocating for meeting occupant needs - could be considered incitement.

So, what are you doing to resist?