The Evolutionary Dualism of our Built Environments

If buildings are a part of the human phenotype as well as a part of our selective environment, what are the implications for design? Part 1 of a series devoted to exploring these implications.

In 1936 psychologist Kurt Lewin first published his heuristic formula of behavior, also known as Lewin’s equation: B = f(P, E), where behavior is a function of the person and their environment. The resulting behavior is often geared to meet the person’s needs that are in turn shaped by the environment. I've always found Meredith Banasiak's, Director of Research at Boulder Associates, use of Lewin's equation in her work insightful. Here’s one of her latest references to it:

Sure, Lewin’s equation is an over simplification (as are equations, algorithms, and models in general) - that’s why it’s often labeled a heuristic formula - but it's still a useful way to frame people's interactions with their environments. Particularly when you think of the environment as both the physical and social/cultural realms, and consider the physiological, psychological, and social/cultural factors that shape a person's (or group's) needs, driving potential decisions and actions.

So, in the formula, people can be an individual, a single group of two or more individuals, or multiple groups (even though Lewin primarily focused on the individual). The environment is both the physical and social/cultural environment of the individual or group(s) in question, and behavior may be that of an individual or group(s) undertaken to meet certain needs. In reality, this complex and varied interaction of P and E is occurring at all levels simultaneously in a nested hierarchy from the individual to the global level.

In her video above, Meredith discusses how we could do a better job of mindfully making buildings more adaptable to meet a greater number of needs that vary by demographic factors, time of day, and over the course of the year. In other words, we can make the environment more adaptable (widen the Goldilocks Zone in a manner of speaking) instead of forcing people to adapt in order to meet their needs and facilitate desired behaviors (often with less success, negative health and productivity impacts, and other unintended outcomes). Buildings in essence are something we shape to meet, or fit, our needs while simultaneously shaping the decisions we make and actions we take within them.

From an evolutionary perspective, this means that buildings are both part of our phenotype as well as part of the surrounding environment that selects for our behavior (and other phenotypic traits). With respect to the former, [j]ust as the shell selecting behaviors, as well as the shell itself, are part of the hermit crab phenotype (the observable characteristics of an individual resulting from the interaction of its genotype with the surrounding environment), so are the behaviors of design and construction, as well as the resulting built environments themselves, part of the human phenotype. The human phenotype consists of biological features (skin color, height, muscle strength, circadian system, basic behaviors, etc.) and cultural features (tools, artifacts, dwellings, institutions, intellectual traditions, etc.) that are the result of, as well as subsequently drive, individual and collective behaviors.

Our phenotype impacts our evolutionary fitness (and we can use our health and productivity as a proxy for evolutionary fitness). The quality of this impact depends on how well the different aspects of our phenotype are adapted to our surrounding environment (physical and social/cultural). And here is where we see the building, as part of the environment, contribute to determining how adaptable different aspects of our phenotype are in a given situation as well as select for specific behaviors (and/or other phenotypic traits). What behavior is being selected for is partially determined by how well we’ve fit our buildings to align with our various phenotypic traits.

If a building doesn’t provide adequate daylight exposure to optimize our circadian system (especially in the morning), or if higher concentration levels of CO2 resulting from inadequate ventilation cause us to feel drowsy and lethargic, we may rely more heavily on caffeinated beverages to help us stay alert and focused, as Meredith alluded to in her video. In this case, certain phenotypic traits related to human physiology aren’t well adapted to the environmental conditions of limited/no daylight exposure and low ventilation rates, resulting in feelings of drowsiness and lethargy.

This has a negative impact on individual and organizational productivity and ultimately fitness levels. This combined physical and social environment then selects for the behavior of drinking caffeinated beverages. So, drinking caffeinated beverages [B] is a function of employees [P] working within their under-ventilated and/or inadequately daylit workspaces as part of an organization that rewards productivity and makes caffeinated beverages readily available [E].

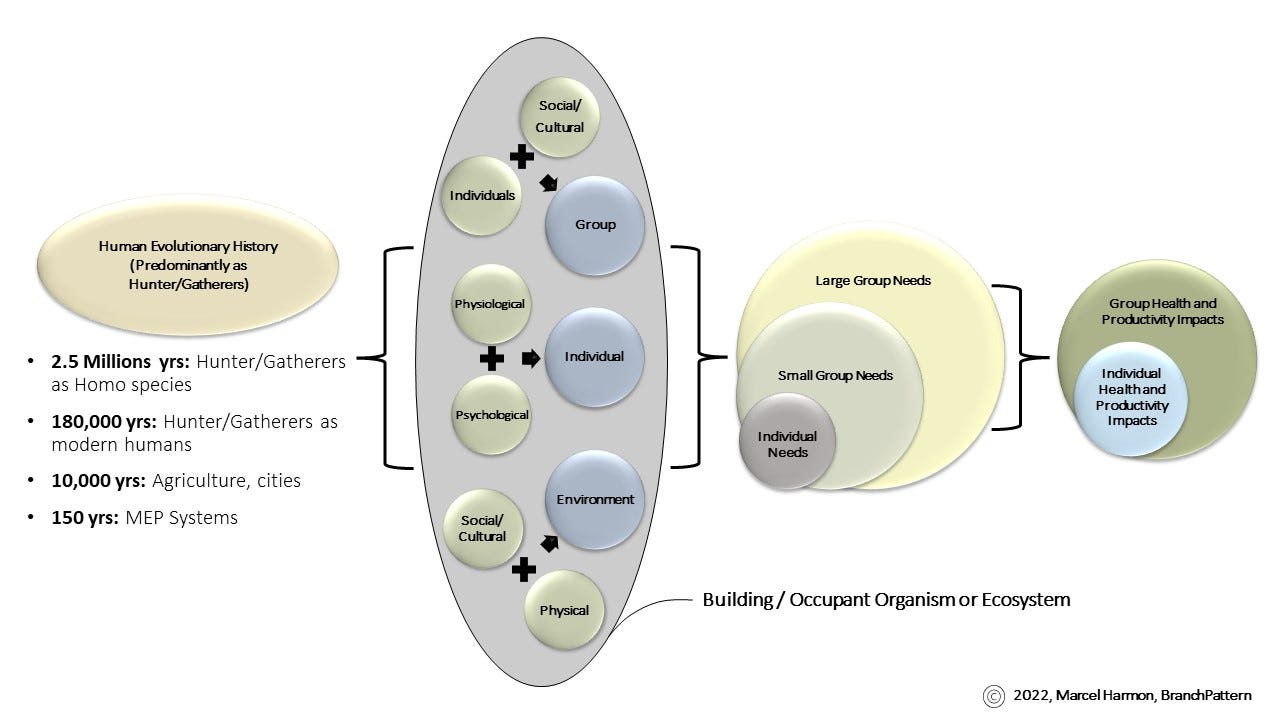

As we think about the complexities of the reciprocal relationships between a) people and buildings and b) people and other people within buildings, along with the external factors impacting those reciprocal relationships, Lewin’s equation loses some of its usefulness as a heuristic (though it’s still helpful as demonstrated above and in Meredith’s video). This is one of the reasons why I developed the figure below, the latest iteration of a graphic I started working on years ago.

Referring to the large gray oval, we can think of the combined building and building population as a building/occupant organism, composed of individual occupants with varying physiological and psychological needs. Organizations, departments, and other formal as well as informal groups of occupants (such as those defined by various demographic factors) are also present within the building, subject to their own formal and informal rules of interaction (policies, norms, etc.), which are in varying degrees of alignment with the formal and informal rules of interaction of other groups within the building, as well as with the larger encompassing communities and society the building/occupant organism resides within.

In addition to the individuals and groups within the building are the environments that shape, facilitate, and constrain the actions of these same individuals and groups. These environments include the physical building itself as well as the social/cultural environment, the latter consisting of the various formal and informal rules of interaction at play, from the organization to the larger encompassing communities and society. All of this together - the individuals, the groups, the physical environment, and the social/cultural environment - compose the building/occupant organism.

As alluded to when referencing the formal and informal rules of society diffusing into the building/occupant organism, its design, construction, and operation occurs within a larger nested hierarchy of groups that extends all the way up to the global level. The needs and goals of these groups vary within each level and between each level, shaped by the various evolutionary forces operating at multiple levels simultaneously - genes, cells, individuals, and at each level of this nested hierarchies of groups. Building phenotypic traits (such as automated shades or skylights) that increase individual occupant fitness levels via facilitating adequate daylight exposure may be perceived as decreasing organizational fitness levels (via increased first cost and/or increased maintenance costs) within a free market economic context that focuses on annual profit margins (while also ignoring impacts on people costs). The degree of alignment and conflict in the needs, goals, actions, etc. within and between levels impacts the strength of the evolutionary forces acting at each level. This ultimately impacts how the building/occupant organism functions, in turn impacting the health, wellness, productivity, and success of the building/occupant organism as a whole, as well as that of its individuals and groups contained within it. There will be more on this in a subsequent article.

Underlying all of this is the fact that the vast majority of our evolutionary history has been spent in a) small groups without nested hierarchies that were in limited contact with people outside of their group and b) physical environments (i.e., mostly outdoors) that differed significantly from our contemporary indoor environments, engaged in activities revolving significantly around hunting, gathering, small group / family interactions, simple governance, and leisure. We only began to congregate in urban environments with increasingly complex social, economic, and governing structures several thousand years ago, and it’s only been within the last 100+ years that we’ve started spending most of our time within artificially controlled indoor environments. This evolutionary history, having shaped our physiological, psychological, and some aspects of our social/cultural needs, in turn shapes and constrains what the optimal configuration of the building/occupant organism should be.

See the following sources for more detailed overviews of this:

Chapter 4: The Building/Occupant Organism, in Inside OUT: Human Health and the Air-Conditioning Era

Blurring the Line Between “Others” – A Practical Application of Cultural Multilevel Selection Theory

Lewin’s equation is still relevant here - none of this contradicts the statement that behavior is a function of people and their environment - I’ve simply added more details to the equation. With one of those details being that the building/occupant organism is both something we create ourselves - its a phenotypic trait like a constructed tool or hermit crab shell - as well as part of the environment that shapes, constrains, and selects for specific behaviors.

For the AEC (architecture, engineering, and construction) Industry, this means we have the ability, at least theoretically, to mindfully create physical and social/cultural environments that a) are better, and more equitably, aligned to our evolutionary shaped needs and b) better facilitate desired behavior (both of which are arguably needed for a building to be truly sustainable or regenerative). The rub being that in this nested hierarchy of groups from the local to global level, higher level community and societal configurations often constrain what can be done at lower levels (with the focus in this case being the level of the building/occupant organism), because evolutionary forces act at these higher levels as well.

What are some of the implications of all this? Well, that’s what this series of articles is going to delve into. So stay tuned.